Then there is a gap in the book’s history, but early in the fifteenth century Bodley 264 was in England, where a second poem about Alexander, this time in English, was added on new pieces of parchment, and soon after this a third and final text was added into the remaining leaves of the second book: a French prose version of the book of Marco Polo. Both parts were then bound together to make one book.

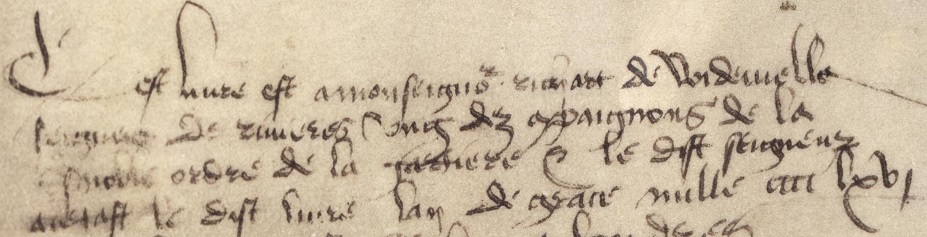

This new book then passed to a series of owners, some of whom wrote their names in the manuscript to indicate their possession of such a prized object. Here you can see where Richard Woodville, Lord Rivers, has written his name (‘de Widevelle’, at the end of the first line) and the date 1466 (‘lan de grace mille iiii lxvi’, at the end of the fourth line):

The inscription (in French) by Lord Rivers at the back of the codex, including his name and ‘the year of grace 1466’.

Click here to learn about how this book travelled around.

Click for more on: owners • the making of books

(Images reproduced by kind permission of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

http://image.ox.ac.uk/show-all-openings?collection=bodleian&manuscript=msbodl264)