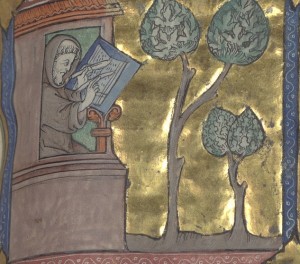

The Renclus de Molliens, pictured writing in his cell in Paris, Bib. de l’Arsenal, MS 3142, f. 203r.

Reproduced by courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France : gallica.bnf.fr/?lang=EN

We do not know the identity of many medieval writers and a large proportion of vernacular (?) works are anonymous. However, some authors cultivated a recognisable literary persona, frequently through self-attribution within their texts. For example, Jan van Hulst names himself in an acrostic in three of his texts in the Gruuthuse Manuscript. Certain authors list the other works they have composed within their latest text (commonly in the prologue or epilogue). This both establishes the author’s corpus and authorises their newest text.

Manuscript compilers also assisted in the creation of author figures. By the late thirteenth century, the question of authorship began to play a role in the compilation of vernacular manuscripts. For example, the identity of the author might be noted in the paratext (?), such as by naming the author in the introductory rubric (?) or closing explicit (?). In illustrated manuscripts, they might even visually portray the poet inside a historiated initial (?) or in a miniature (?), as demonstrated by this author portrait of the Renclus de Molliens.

However, the naming of authors in manuscripts was not always consistent or systematic. Pieteren den Brant is one of the few named authors in the Geraardsbergen Manuscript. In the Berlin manuscript, one of the three named authors might not have used his real name but an aptronym; the other two, though, offer interesting insights into the cultural context of the codex. Find out more here.

In the large thirteenth-century French codex, BNF, fr. 837, the majority of works are anonymous, but one author gets to play a starring role. The works of the famous thirteenth-century poet, Rutebeuf, are grouped together and form a ‘book’ within the codex. Learn more about this early example of an author collection.

Whereas authors composed texts, scribes were responsible for copying their works and ensuring their wider transmission. However, the distinction between ‘scribe’ and ‘author’ is not always clearcut.

Unlike the printing press, scribes were very inconsistent copying machines. The lines they transcribed bear the indelible imprint of human wiles and idiosyncrasies and the evidence of both good days and bad days. In the Geraardsbergen Manuscript, the scribe (who may also have been the owner of the codex) realises that he has missed two lines from a text and corrects his mistake. Find out more here.

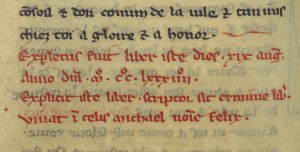

The scribe names himself after having transcribed Brunetto Latini’s Li Livres dou Trésor.

Paris, BNF, fr. 12581, f. 229v.

Reproduced by courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France : gallica.bnf.fr/?lang=EN

Certain scribes appear to take a deliberately interventionist approach, adapting the material in their exemplars (?) or appropriating the texts according to their own designs. The scribe who acquired Bodley 264 attempts to ‘complete’ the Roman d’Alexandre with an episode from an English poem. Click here for more information about this intriguing addition.

As the book trade developed, scribes were no longer located only in scriptoria (?), but were professionals based in urban workshops. You can find out more about developments in book production here. Some scribes therefore had commercial gain in mind and exploited every occasion to market their skills by naming themselves.

The role of the illuminator (?) had also developed into a professional activity by the thirteenth century. These artists therefore shared the same commercial concerns as their colleagues in the workshop. In the lavishly decorated manuscript, Bodley 264, the illuminator Jehan de Grise, evidently proud of his work, names himself and the date he completed his beautiful illustrations.

In addition to scribes and illuminators, rubricators (?) also played a role in manuscript production, adding rubrics (?), simple coloured initials or paragraph markers. Depending on the context of production, sometimes the scribe also completed the rubrication. You can find out more about the decoration of manuscripts here.