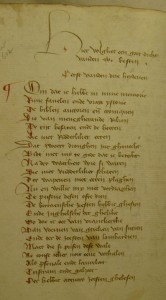

Geraardsbergen Manuscript, Text 89 (fols. 170v-183v)

In the Middle Dutch poem Van den Negen Besten (The Nine Worthies) the nine greatest rulers of the world are portrayed. Three of them are pagans, three are Jews and the other three are Christians. Three is the number of the divine trinity, the perfection. In this text we are shown three times three: the perfect perfection!

This is a good example of numerology. Symbolic use of numbers has always had a major appeal to people, also in the Middle Ages. Many intricate examples of medieval numerology are known. A simple case as three times three, as we find here, is not a surprise in a codex. But is it really that simple?Three copies of Middle Dutch The Nine Worthies have survived the ages, one of them in the Geraardsbergen Manuscript. The Dutch scholar Hubert Slings has shown that this copy has some features the other copies do not have: each description of a ruler contains 40, 80 or 120 verses. The number 40 plays an important role in the structure of the text. The two other copies of the text have more irregular numbers of verses for each ruler.

According to Slings, this structure around the number 40 did not exist in the original source and is therefore presumably added by a later editor. The number of verses has been adapted to be precisely 40 or a multiple of 40 by adding or deleting a few verses where necessary. The editor also paid attention to the overall structure. Here, the number of divine perfection can be found again, for there are three parts of 40 verses, three parts of 80 and three parts of 120 verses (excluding the prologue and epilogue).

In the Geraardsbergen Manuscript the description of the ninth worthy, Godfried of Bouillon, ends abruptly after 72 lines. Since there are already three descriptions of 40 lines and three of 80 lines, this description would have been the third with 120 lines. This means that at least 48 lines are missing, but possibly 88, since an epilogue of 40 lines is to be expected. For these missing lines the scribe would have needed at least two extra leaves.

But why did the editor go to all this numeral trouble? Would readers have been able to detect the elaborate structure? At this stage we can only guess:

- Maybe the copy in the Geraardsbergen Manuscript was copied from a manuscript with 40 verses per page? Because of the different layout in the Geraardsbergen Manuscript the structure of the text was not visible anymore.

- The importance of numerlogy in the Middle Ages does not necesarilly imply that the average (wo)man could recognize the symbolic use of numbers (e.g. in architectural proportions)?

- Numerology did not have a esthetic function, but was applied to give praise to God, by paying extra attention to the form of the text and using meaningful numbers?

What do you think?

And how can this fit in in one of the five stories about the Geraardsbergen Manuscript?

Return to: The Nine (mutilated) Worthies