In the era when papyrus was the most important writing support (?), the best way to keep a long text safe was to roll the interconnected sheets of papyrus into a roll (or scroll). Papyrus could not be folded without risk of breaking it. This did not mean that reading a roll meant unrolling all of it at once. It was read horizontally, so that while rolling out one side, one could roll in the other.

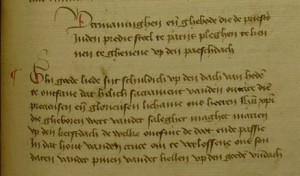

At the dawn of Christianity the roll was supplanted by the codex, a bound book. The first codices were made of wooden writing tablets, hence the name ‘codex’, which is derived from the Latin word caudex (‘a block of wood’). The invention of parchment changed the codex drastically. Exploiting the flexibility of parchment, which did not break when folded, books were from then on made of many thin layers of animal skins.

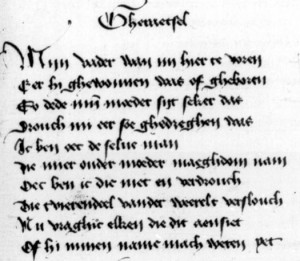

But the codex did not replace the roll entirely. Parchment rolls continued to be used throughout the entire medieval period. For texts that had to be proclaimed, a roll was often more suitable than a book: we can all picture a herald in a town square reading a message from the king.

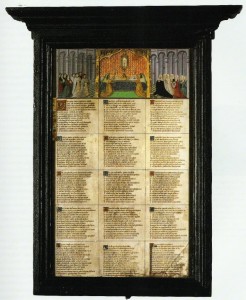

Long genealogies too were drawn on large parchment rolls, stitching skins together when the family trees grew over the original borders of the sheets. A fifteenth century example can be found in Chicago’s Newberry Library.

Although the monks in this video look a little too modern to have witnessed the initial change from roll to codex, their reaction to the new invention may be spot on!

Return to: The Making of