The Geraardsbergen Manuscript is a simple codex from the fifteenth century, which contains a collection of almost 90 texts from a wide range of genres. The scribe who copied these texts into the codex must have had considerable experience in writing books, but he did not taken great pains to produce this particular manuscript. He hardly used any rubrication and he arranged his collection in an disorderly, sloppy way, with many blank spaces in between the texts. All this gives the book a very ‘personal’ look, which makes it not unlikely that the scribe was also the first owner and that he made the manuscript for his own use.

The codex has been named the ‘Geraardsbergen Manuscript’ by modern scholars, because in its contents there are clear pointers to the Flemish town Geraardsbergen (Grammont), situated south-west of Brussels. These pointers are a famous inn in that town (‘Inden vranxschen scilt’ – ‘In the French Shield’) and two men: Perceval vanden Noquerstocque, who was a priest in Geraardsbergen and member of a patrician family there, and Pieteren den Brant, who is often found in archival records as an organizer of cultural events.

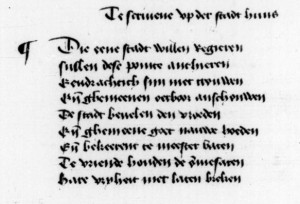

The Geraardsbergen Manuscript is not only interesting because of its diverse contents, but it also gives us an idea about the cultural life in a medium-sized town in Flanders in the second half of the fifteenth century. This cultural life turns out to have more aspects than one would expect from general overviews in literary histories. The manuscript contains many different types of texts, for instance riddles; captions in Latin, French or Dutch to be written next to paintings, statues, mirrors or even the door of a toilet; itineraries; religious texts on the right way to say confession or the manner in which one can help a dying person to pass away in peace. One of these texts was meant to be posted on the church wall, others were clearly meant for private use. And then we have some narrative verse texts; a letter in verse; even a sermon; popularized scientific information; calendars; and a world history in ‘Reader’s Digest’ format. Going through the manuscript’s contents gives us an insight into the remarkable diversity of medieval culture.

But on the other hand, this diversity makes it difficult to determine the status of this manuscript. Modern scholars have proposed very different hypotheses about the use of the collection and the identity or the social status of the original producer/owner of the manuscript. Every codex tells a story? Well, this one tells at least five!

See also:

- the table of contents

- a codicological description of the manuscript

- a discussion on the origins of the manuscript: five different opinions

- the owners, readers, writers and other people connected with the manuscript

- suggestions for further reading