Author Archives: nzotz

Why Put Them Together?

- The texts in the booklets were quite new at the time.

- They were written by local authors of high standing.

- They were collector‘s items.

- They represent the connection of two noble families (which can be concluded from the names in the manuscript).

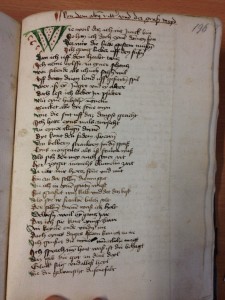

Beginning of ‘Die Grasmetze’ by Hermann von Sachsenheim; Berlin, SBB-PK, Ms.Germ.Quart 719, fol. 196r.

It is obvious that the texts are interesting for different readers, catering to all tastes from the didactic to the erotic, and they also are a form of noble self-representation (like status symbols). Maybe not on a material level, since what you see here is the most elaborate page in a fairly average manuscript.

But the content – texts about love – seems to have worked as a means of representation: the texts show the marital and literary conjunction of two noble houses. They fit together well (as does the book). The only puzzling thing in this context are the prayers which seem quite out of place in this manuscript. But there might be one explanation for them which would also help us date the manuscript.

There is another manuscript from the same period that also shows how texts about love could function as a noble representation.

Solution to the German Riddle

zwyernet fünff und eynß me

der fynffzehenst bustab am abc

bedrigt den man und nit me

Which means: ‘Woman betrays Man and (does) nothing more.’

Go back to the riddle.

A Medieval German Riddle

zwyernet fünff und eynß me

der fynffzehenst bustab am abc

bedrigt den man und nit me

Two times five and then add one,

The fifteenth letter of the alphabet

Betrays men and nothing more.’ –>Solution

What the Names Tell Us

Wameshafft (MHG Original Text)

Hie mit die red sich fullent

die ich duommer wameshafft

uß schlechttem sin an meinsterschafft (!)

zu küngsteyn uß syennen brach

fyer wochen was ich cranck vnd swach

daß ich das lant mocht bruchen niht

die will maht ich duß nü gedicht

myner genedigen junckfrawen hab ichß geschenckt

dass got des frumm herrn gedenck

vnd behuet sin son das edel bluot

wan sie mich detten alles gut

spis und dranck mit willen gern

got well die dugent rich gewer.

Go back to the information on Wameshafft.

Erhard Wameshafft

Here now end the words which I, the dumb Wameshafft, did produce from meager mastery, at Königstein. I was four weeks so ill that I could not roam the lands. While I was ill, I made this new poem and I gave it as a gift to my graceful young lady, that God might remember the Lord and guide his noble son, because they did many good deeds and gave away food and drink willingly; God will reward the virtuous.

(View the original MHG text).

Hermann von Sachsenheim

The Book and its Users.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz (SBB-PK), Ms.germ.qu. 719

We have three authors named in the manuscript, Hermann von Sachsenheim, Erhard Wameshafft and Schoffthor. The last one remains just a name to us (an aptronym, denoting a writer as foolish as a sheep). But the other two give important clues for the world around the manuscript.

Read about Hermann von Sachsenheim.

Read about Erhard Wameshafft.

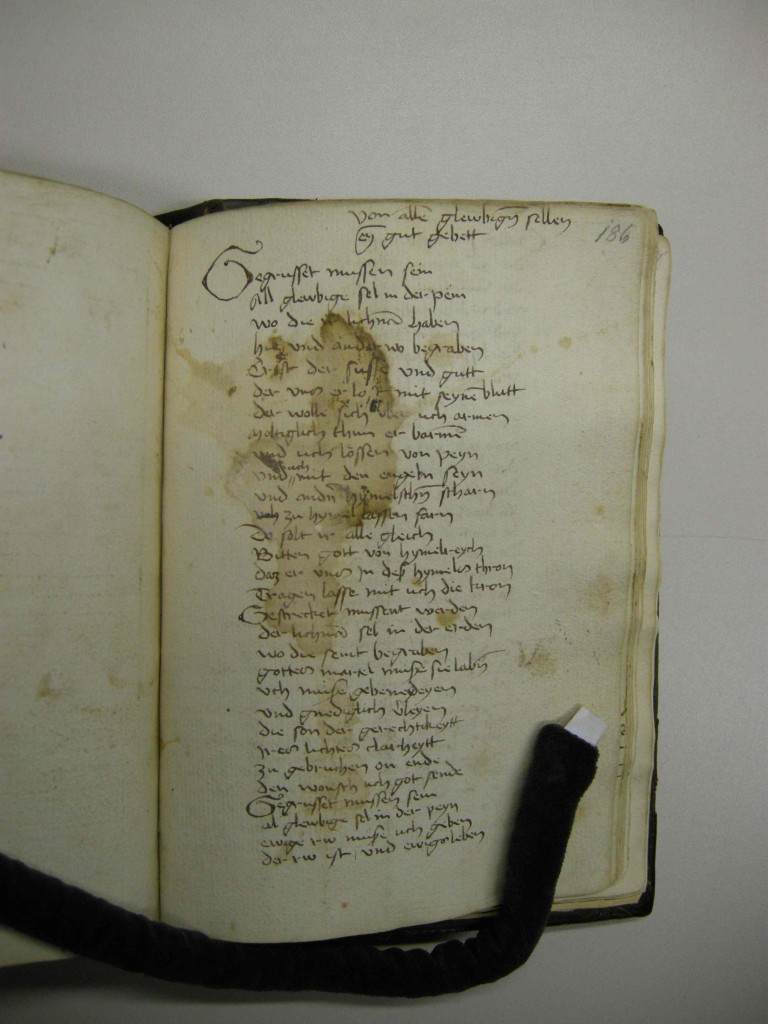

Booklets Bound Together

Most of the booklets end with empty pages, a clear indication that the book was not written continuously. Thus, for the making of the book as interesting as the texts are the empty pages in the manuscript. Empty are: 60v; 65v-67v; 101v-102v; 181v-185v; 191r-195v. Furthermore, the outer pages of the booklets show signs of use – they not only lay on a shelf, but were read quite frequently before being bound together as a book. Have a look for instance at the stains at the beginning of the 5th booklet: