BNF, fr. 837 contains a wide range of texts; sacred and secular, edifying and rude, supernatural and mundane.

These include:

love poetry, prayers, paternosters, credos, abcs, funny stories, rude funny stories, tales of adventure, moral and edifying stories, astrology, texts about women, fables, love stories, saints’ lives, beast epic, tales of Heaven and Hell, texts about wine, historical notes, allegorical works, plays and dialogues, proverbs

Paris, BNF, fr. 837 (pre 1300), ff. 66v-67r

Reproduced by courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France: http://gallica.bnf.fr/?

Here, a retelling of the Prodigal Son story (Cortois d’Arras) is juxtaposed with a fabliau, Boivins de Provins.

The last line of Cortois and the first line of Boivins are only a few lines apart. They are, respectively:

‘Chantons de deus laudamus’

(Let us sing about God; let us praise Him.)

and

‘Molt bons lechierres fu Boivins’

(Boivin was admirably fond of the pleasures of the flesh.)

This rather brings out the contrast between the two texts, but also suggests that medieval readers liked a variety of different types of reading matter.

In terms of moral viewpoint, the two texts are worlds apart. Cortois implicitly condemns both the sin of frolicking with prostitutes and the sin of pride, and believing oneself more entitled than others. What is important is forgiveness, even and especially of the unworthy.

Boivins, meanwhile, adopts a different stance. The main character carries out a complicated ruse in order to obtain free food, drink and sex, and is thought to be rather clever for doing so. It is patently amoral.

The form of the two texts is also different. Cortois is almost entirely dialogue, whereas Boivins is a story with a narrator.

However, there is an important similarity: in both cases, a sizeable proportion of the text is a scene at a brothel with two women attempting to swindle a man.

The main difference is that Cortois loses all his money to the women, whereas Boivin is tricking the women into thinking they are swindling him, while he swindles them. He is pretending to be what Cortois really is: an innocent, ready to be fleeced.

This really brings home how very interconnected medieval literature is, and makes us aware of the limits of genre labels: two texts, nominally belonging to different genres, may still have a lot in common.

Of course, many of the genre labelling words we use are largely the product of modern criticism. The word ‘fabliau’, for instance, did exist in medieval French, but it is used now to mean short stories in verse, mostly funny and sometimes rude: there is a (debated) canon of fabliaux, which includes many texts that do not call themselves fabliaux, and excludes some texts that do.

This particular manuscript does have a genre labelling system, but some terms within that system seem more straightforward than others. The term ‘patrenostre’ is one which is clearer in meaning.

Edited paternoster

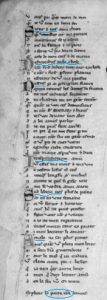

Paris, BNF, fr. 837 (pre 1300), f. 247v (detail).

Reproduced by courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France: http://gallica.bnf.fr/?

The manuscript contains several texts which are labelled as a ‘patrenostre’ in the explicit.

This is the end of a ‘patrenostre d’amours’, with the word ‘patrenostre’ in the explicit circled in blue.

The same format is used for all the ‘patrenostres’. The Latin text of the pater noster (Lord’s prayer) is broken up into small chunks, and used as a frame for the French verse text, which is sometimes a translation and expansion of the Latin, and sometimes utterly unrelated. The Latin framework is underlined in blue. As you can see, it forms a fairly small proportion of the text.

Here is another extract, transcribed and translated.

‘Sanctificetur…’

Paris, BNF, fr. 837 (pre 1300), f. 247r

Reproduced by courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France: http://gallica.bnf.fr/?

‘Sanctificetur. Douce dame

Qui es sauveresse de m’ame

Quant del cors me departira

Et li angeles l’emportera

Dame se deveniez m’amie

Molt en seroit mieudre ma vie

Nomen tuum. veraiement

m’est vis qu’ele est apertement

la plus bele…’

‘Hallowed be. Sweet lady

you who are the saviour of my soul

when it leaves my body

and the angel takes it away;

Lady, if you were to become my lover

my life would be much better.

Thy name. Truly,

I think that she is obviously

The most beautiful of all women…’

An ‘ABC’

Paris, BNF, fr. 837 (pre 1300), f. 170v (detail)

Reproduced by courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France: http://gallica.bnf.fr/?

Other similar genres are ABCs and Credos, which work in the same way, insofar as they have a framework (the alphabet or the Latin Credo) which is amplified with French verse.

For the terms fable, fabliau, dit, conte and ditié, things get rather more complicated.

Sometimes they seem interchangeable, but at other times they are used as if they have quite distinct meanings: even within this one manuscript.

Paris, BNF, fr. 837 (pre 1300), f. 199r (detail)

Reproduced by courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France: http://gallica.bnf.fr/?

Here, the words ‘conte’ and ‘dit’ appear to be used interchangeably: the word ‘conte’ is used within the text to refer to the text, but the explicit calls it a ‘dit’.

At other times, the impression is given that these words do have meanings, and mean different things. The beginning of this story, for example, sets up an opposition between ‘fable’ (made up stories) and truth.

Text opening with ‘fable’

Paris, BNF, fr. 837 (pre 1300), f. 265v (detail)

Reproduced by courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France: http://gallica.bnf.fr/?

‘Whoever makes rhymes or fables

Instead of telling you a fable

I will tell you an adventure that really happened:

Who it was about and how it ended.

I will tell you the truth about it.

It came to pass in a city

That there were two money-changers…’

Another text begins: ‘People make fabliaux out of fables, and new notes out of sounds…’

Next: Rutebeuf: an author apart