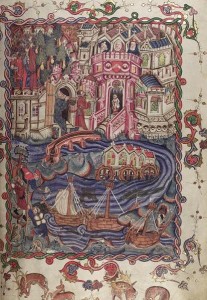

Although we now think of Bodley 264 as a single book with one name, it is actually made up of three pieces, made in different places more than 60 years apart. It began life as a copy of the long French poem about Alexander the Great, called the Roman d’Alexandre. We can tell from the style of the illustrations that this was made in Tournai, now in the eastern part of Belgium, but then part of the Kingdom of France. We can also date this part of the manuscript to 1344, the date when an illuminator (?) called Jehan de Grise wrote a note to say ‘Che liure fu perfais de le enluminure / au xviii jour. dauryl . per iehan de / grise.. lan de grace. m. ccc. xliiii.’ [‘This book was completed with its illuminations by Jehan de Grise on the 18thday of April in the year of grace 1344’]

The original owner hasn’t left any signs of their ownership, so we can’t tell who it was made for, although it is probable that such a de luxe product was made to commission for a wealthy and aristocratic owner.

A few decades later, with a new owner, the book began to grow.

Click for more on: scribes • owners • manuscripts linked to particular places

(Images reproduced by kind permission of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

http://image.ox.ac.uk/show-all-openings?collection=bodleian&manuscript=msbodl264)