If people use the word ‘text’ today, they can mean quite different things. The word can designate a whole book, or parts of it; if stories are collected and presented in the frame of a larger story, ‘text’ can refer either to the frame story or to the smaller stories. And although we usually think of texts as written, they can also be spoken.

The Middle Ages did not have a similarly broad concept of text. There is a large variety of terms designating what we would translate by ‘text’ (book, story, tale, history, news, etc.). Nevertheless, by looking at tables of contents (see Medieval Inventions) we can see that people had quite a clear concept of ‘textual item’: texts were counted, numbered, referred to, even if they were not called ‘texts’.

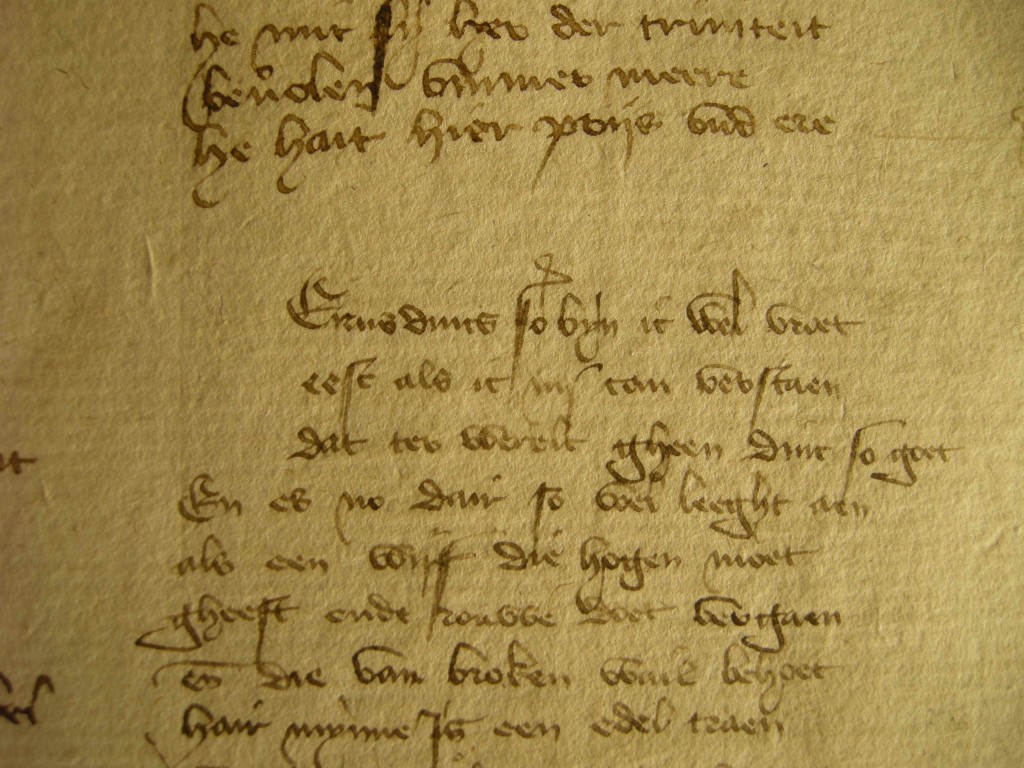

To make things simple, we use the modern term ‘text’ in this exhibition to designate one item in a book, meaning a coherent number of sentences, normally divided from another text by at least some blank space in the manuscript, often also an initial (?) and sometimes a rubric (?) giving a title or an author or summarizing the content of the following. In this example, the blank space clearly indicates where one text ends and the next one begins (the scribe has left some space for an initial to be filled in later by the rubricator (?), but this never happened).

In our project, we are looking at the treatment in the manuscripts of a specific kind of text: the short verse narrative.